The Transitional Orson Welles

The Transitional Orson Welles

Late Works and Adaptations

AUGUST 1-15, 2008

Co-Presented by Richard Hugo House

It is ironic that the three literary adaptations Orson Welles made in the 1960s are the least seen of his films, yet comprise some of his best and most adventurous work. He filmed Franz Kafka's THE TRIAL in 1962, CHIMES AT MIDNIGHT in 966 (Welles' version of Shakespeare's chronicle plays), and Isak Dinesen's THE IMMORTAL STORY in 1968. All three were shot in Europe, after Welles' second departure from Hollywood.

NWFF is pleased to (re)introduce Seattle to this least explored era of one of cinema's iconic yet misunderstood directors.

Series passes $10/NWFF members, $15/general

Sponsored by Scarecrow Video

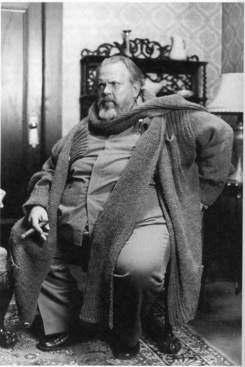

Chimes at Midnight

Sponsored by Scarecrow Video

Aug 08 - Aug 10, 2008

Orson Welles, 35mm, France/Spain/Switzerland, 1966, 113 min

This is one of the great Shakespearean adaptations and a true "lost classic." It's also the last masterpiece that Orson Welles directed, and, with CITIZEN KANE, MAGNIFICIENT AMBERSONS and TOUCH OF EVIL comprise the quartet of his major cinematic achievements. The film is an inventive re-editing and condensation of Shakespeare's historical works. Welles assembled scenes from RICHARD II, HENRY IV PARTS I AND 2, HENRY V, and THE MERRY WIVES OF WINDSOR, along with a commentary taken from the chronicles of the Elizabethan historian Holinshed, to create a wholly new work that might alternatively be titled "The Tragedy of Sir John Falstaff." The film focuses on the character of Jack Falstaff, played by Welles in a virtuoso performance. Falstaff's relationship with young Prince Hal (later Henry V) is explored and parallels Welles' own experience with the young talents of Hollywood.

"If I wanted to get into heaven on the basis of one movie, that's the one I'd offer up." - Orson Welles on CHIMES AT MIDNIGHT

Opening Night Introduction from Seattle Shakespeare Expert Bill Matchett Discussion after Friday 7pm screning with playwright Dickey Nesenger

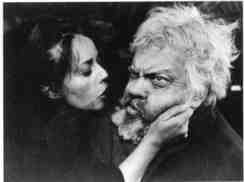

The Immortal Story

Sponsored by Scarecrow Video

Aug 15 - Aug 17, 2008

Orson Welles, 1968, France, 16mm, 63 min

In a mansion in Macao at the turn of the last century sits an aged merchant, Mr. Clay (Welles), with no family and nothing to do but contemplate his fortune. Mr. Clay believes in power, not in prophecies, facts, not stories. So he decides to make an oft-repeated seafarers’ fable come true, enlisting an aging beauty (Jeanne Moreau) to play his young bride, and a virginal sailor to enact the plot and later tell the tale. But some stories must remain untold—truth is their undoing. Welles adapts Isak Dinesen’s parable in melancholy tones, draping layers of narration over deep-focus images of ornate chambers and crumbling squares, with music by Erik Satie setting a measured rhythm. “By my brain and by my will, many things come together,” Mr. Clay says, and one could easily read his story as an allegory of moviemaking, his character somewhere in the margins between playing director and playing God.

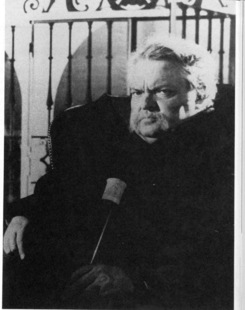

The Trial

Sponsored by Scarecrow Video

Aug 01 - Aug 03, 2008

(Orson Welles, France/Italy/Germany/Yugoslavia, 1962, 35mm, 118 min)

In 1962, when the noir style was in decline, Welles agreed to direct a black-and-white adaptation of Franz Kafka's THE TRIAL. It wasn’t Welles’s first choice for a Kafka adaptation—he preferred THE CASTLE—but he called the end result “the finest film I have ever made.” The film was so successful in combining the elements of noir and Kafka that it came to define the term "Kafkaesque." Josef K (Anthony Perkins) is arrested for an undisclosed crime by police straight out of a "B" movie. The search for justice, or at least an explanation, leads him past desolate Zagreb apartment blocks to the abandoned Gare d’Orsay, a shifting maze of offices and vast halls inhabited by bureaucrats and the condemned waiting for fate to call their number. Balancing the baroque expressionism of Welles’ visual style are a script and performances—including the squirming Perkins and Welles as the Advocate—that emphasize the affinity between nightmare and comedy.

"Given the impact of screen size on what he’s doing, you can’t claim to have seen this if you’ve watched it only on video." -Jonathan Rosenbaum